The King of Concrete: Si Pilimon’s Empire of Dust

In Congressman Si Pilimon’s district, a freshly paved highway glistens under the midday sun, its blacktop smooth and unblemished. It’s the third time this stretch has been torn up and rebuilt in six years—each time declared “urgent” in the General Appropriations Act (GAA), each time a windfall for the contractors in Si Pilimon’s orbit. Locals watch in quiet disbelief as jackhammers shred perfectly good pavement, the rumble of machinery drowning out their murmurs. “Why destroy what works?” they ask. The answer lies in the 20 to 30 percent “SOP” kickbacks Si Pilimon pockets per project—easy money flows faster when you rebuild what doesn’t need fixing.

Meanwhile, in the mountains that cradle his district, roads crumble into muddy scars. Landslides bury villages after every monsoon, cutting off farmers who trek hours to market over paths no vehicle can navigate. These rugged trails, crying for repair, see no bulldozers, no budgets. Si Pilimon’s gaze never lifts to the highlands; his empire thrives on flatland highways and flood control walls, projects ripe for skimming, not the hard labor of mountain infrastructure.

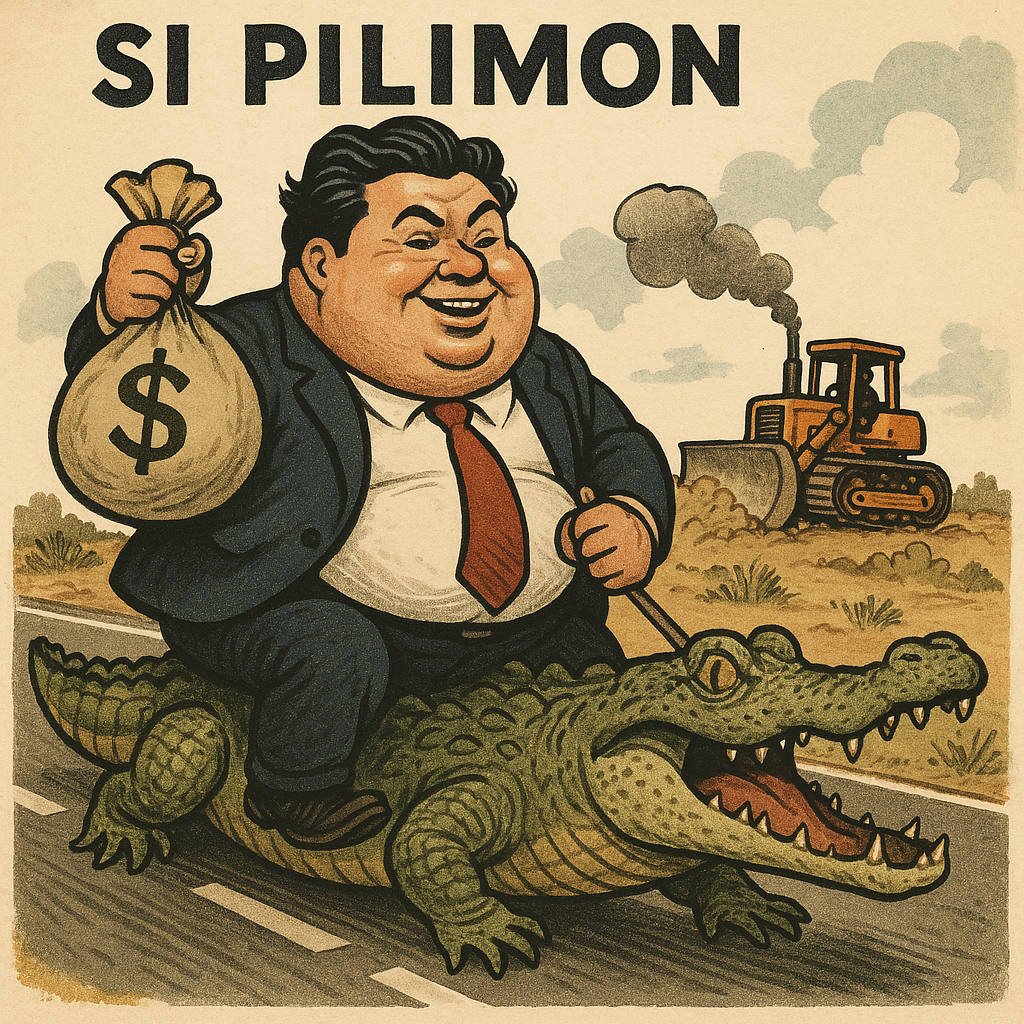

Si Pilimon is a colossus of Philippine politics, his corpulence rivaled only by his hunger for wealth. Nine years in Congress have left his legislative record as barren as the mountain roads he ignores. No economic zones, no job programs, no vision—just a sprawl of concrete legacies: roads repaved to oblivion, flood controls that fail, and a bridge locals call Tulay sa Wala—the Bridge to Nowhere—its ends swallowed by weeds. He is no lawmaker but a contractor in a barong, his family’s firms shadowing every GAA insertion he muscled through the Countrywide Development Fund (CDF).

The scheme is brazen yet routine. A P100 million highway “rehabilitation”—even when the cracks are imaginary—yields P20 to P30 million in commissions, siphoned through loyal intermediaries. Why build anew when you can destroy and rebuild, each cycle a fresh payday? Flood control dikes wash away, only to rise again at triple the cost. A multipurpose hall no one uses sits overbudget and empty. Si Pilimon’s district is a canvas of waste, painted with taxpayers’ money and framed by his mansion’s gilded gates.

He is not alone in this game; he is its master. The CDF, meant to spark local progress, is a slush fund for the cunning. Oversight falters—audits vanish, whistleblowers fade—and voters, tethered by handouts or habit, keep him enthroned. His SUVs roll past shanties, his laughter rings at ribbon-cuttings for roads already fading under the next rain. To his people, he is both benefactor and thief, scattering gravel while hoarding gold.

The absurdity peaks on the lowlands, where highways are demolished and reborn, while mountain folk cling to cliffsides, their pleas for passable roads unanswered. A farmer in the uplands, Mang Tino, lost his harvest last season when a washed-out trail stranded his crops. “We need a road to live,” he says, voice rough as the stones he walks. Down below, Si Pilimon’s latest project—a redundant repaving—grinds on, the sound of profit drowning out Mang Tino’s despair.

Yet cracks appear in Si Pilimon’s dominion. At a town hall, a young woman rises, her eyes sharp. “Why tear up good roads, congressman? Why no help for the mountains? Where are our jobs?” The crowd hushes. Si Pilimon shifts, his smile a mask, and mumbles about “infrastructure as growth.” Applause follows, but her words pierce the air, a challenge unmet.

Reform glimmers on the horizon, faint but fierce. It demands dismantling this machine of patronage—reining in the CDF, exposing the commissions, and turning voters’ gratitude into scrutiny. It means leaders who prioritize need over greed, who see mountain roads as lifelines, not just lowland cash cows. Si Pilimon’s empire of dust can crumble, but only if his district’s voices—Mang Tino’s, the young woman’s—grow louder than the jackhammers.

For now, Si Pilimon reigns, his bulk casting a shadow over ribbon-cuttings and ruined dreams. The highways gleam, the mountains wait, and the commissions flow. But a reckoning brews. In every barangay, in every heart weary of waste, a chorus rises. It is soft, but it builds. And when it thunders, even the king of concrete may fall.